The Waulkers “dressed” and “fulled” the cloth. Their webs were often taken to Waulk Mills in country areas around the Burgh for processing. However they were members of the Nine Incorporated Trades of Dundee. This gave them much greater authority in the Burgh and indeed, through the Nine, a right to seats on the Burgh Council.

On the other hand the Listers or Dyers were very few in numbers.

Until as late as the 18th Century, Sumptuary Laws, which limited private expenditure in the interests of the state, dictated how the various classes could be dressed. The vast bulk of the people, the poorer Scots, therefore wore rough garments of white or grey cloth which was neither fulled nor dyed. It is interesting to note that legally only whores were allowed to dress above their station. Presumably the numbers of people who could wear dyed cloth was very limited.

Another reason for the small numbers was that Blaksteris, who used bark to produce black dye, were allowed to practise outwith the Craft (the bark used for this purpose came from the oak tree and is one of the reasons for the disappearance of these trees in Scotland). Even worse, Guild Brothers and Merchants, with some restrictions, were allowed to set up their own vats and dye material in any true colour. They could also employ anyone to do this work. Bonnetmakers were also allowed to dye their own bonnets. All of this left very limited employment indeed for the poor Dyers.

The two Trades led individual lives until the time came when they could see that it was to their mutual advantage to unite into a single Craft.

Their contract of union was prepared and signed on 3rd May 1693, and the union completed by a Charter signed by William & Mary, at Kensington 28th February 1694 and ratified by the King and Estates on 17th July 1695. Thus the whole body of Listers was absorbed into the Waulker Craft, and the united Craft became known as the Waulker Craft and Incorporation, later changed to the Dyer Craft. The name change to the Dyer Craft came about gradually towards the end of the 19th century. We do know that, however, at the time of the amalgamation there were only ten Listers and five Waulkers in the two Crafts.

Prior to that things had not always been so friendly. On 29th May 1604, John Lamb, a dyer, was found guilty of calling John Sym (the Deacon of the Waulkers) a thief and threatening to hang him. There must also have been problems with the undercutting of prices between the Crafts. On 23rd May 1672 the Waulkers passed an act fixing the price of their work. Six members met and decreed “to take no warke or dressing or thicking of cloth from Listers in Dundie and agrie or exact any les pryce therfor then ye pryces following. To witt four shilling Scots for ilk ell of broad cloath for thicking and dressing. Item for thicking and dressing ilk ell of narrow cloath ane shilling sex pennyes Scots money. Item for thicking and dressing of broad cloath thicket befoir fowrty pennies. Item for dressing of thicket narrow cloath twell pennyes. Under ye pain of ten punds Scots money toties quoties to be payed evrie transgressione for ye use of ye Craft be ye transgressor, and ye challenger or acuser not making it evident appear yt ye Delinquent be fyned & convict to pay fortie shillings for ye use of ye craft besyd Expense of conveining at the Deacons discreatione.” Whilst ensuring that there was no unfair undercutting of prices, one Master falsely accusing another Master of the Craft was very heavily punished.

Dyers as a Trade were always struggling to find enough members to keep the craft alive and indeed by 1823 there was only one member in the joint Craft. The Nine Trades could not let the Trade fall for lack of numbers and therefore appointed three managers to the Incorporation of Dundee, allowing them to give admission on the usual terms to apprentices and others applying to become members. On 12th October 1840, these managers admitted: Alex. J. Warden, manufacturer and dyer; Chas. Norrie, merchant and dyer; and David Halley, merchant and dyer, in Dundee, to be free members of the Incorporation. However, because none of the three was a practising dyer, although they were dyers on an extensive scale by employing many men in the dyers trade. Objections were made to their admission. This was tested in The Court of Session, who found against the three. They were repaid their dues and renounced their interest in the Trade. Shortly after this several new, practising dyers were admitted into the Craft, thus keeping it alive.

Quoting from the Laws of the trade, after the payment of his dues the apprentice “Shall immediately receive the word, with tokens sufficient to answer that he is lawfully brothered to the trade professeth”. Later in the Laws a fine of sixpence was to be imposed on any apprentice who revealed the “Word, Chap or Whistle” to any person, apprentice or journeyman before he was entered as a brother. These references have obvious overtones of Masonic ritual. Although the trades were reputed to be associated with Freemasonry there is no direct reference to this in any documents that have yet come to light. Only in one minute, when discussing the various processions in which the Crafts took part, does it state that Masters should process with their Craft “unless processing with their own Lodge.”

The early form of oath taken by entrants to the Craft and dated 9th April 1529 states:–

“I shall obey the eternal Lord my God, creatour of heaven an earth. I shall maintaine, fortifie and defend his holy gospell presently profest amongst us, so far as lies in me. I shall declin at no time therefra, I shall be loyall to our soueragin the king and his successors, to Prouest and bailies of this brough, and to the deacone and members of the Incorporation – I shall make concord among the brethern where discord is – I shall fortifie the common weall – I shall us myself cristianly in my calling , and shall us no fraudfull dealing in my craft – I shall relieu the poore and neide, and help and support the widows and orphans according to my pouer – I shall assist my brethern of the Craft in all respects that tends to the welfar thereof. I shall com to oney plac apointed for conuientione and giu my best aduice to my brethren. – I shall neur contrawen directly or indirectly my saids brethern of craft – I shall be na mutineir nor raiser of tumult, and shall obey all Laus and Saitutis made and to be made for the wellfoir of the said craft – And this I promise, God helping me.”

The wording of the oath is similar to that of most of the other Crafts, suggesting that the clergy had a hand in the formulating of them. In particular the use of the phrase regarding religion as “presently profest amongst us” allows for all the changes taking place in religion in Scotland over the years before and after the Reformation. Dundee was in the vanguard of these changes and was known across Europe as “The Geneva of the North”.

Aprenticeships, leading to Journeyman status, varied in length over time of from five to six years. In addition the apprentice had to serve at least two years as a Journeyman before he could be considered a Master. In addition he had to prove that he was a capable tradesman by performing an ‘essay’ or ‘masterpiece’. This piece of work had to be examined and approved by three existing Masters of the Craft. Only after this could a Journeyman, as he was then called, become a Master. However, this was an expensive undertaking. Firstly he had to become a Burgess of the town. This was difficult but despite the cost it was the only way in which he was allowed to trade and do business in the Burgh. In addition, as a Master he would have to own his own equipment, a house in which to house his Apprentice, and a wife to care for them. The apprentice would live with the family and be bound to them for the period of his Indentures. The Master was permitted to punish him in any way he thought fit and the apprentice could not move to another Master until he had completed his full indentured time. Finally, on being admitted as a Master, in 1709, his dues to the trade alone were four hundred merks.

The whole business of apprenticeships was fraught with problems and costs, both for the Master and his apprentice. For example, in 1694, “non of the members of s(ai)d trade shall take ane prentise but once ilk sex yeirs, so that no Master can have two prentises togither……and albeit any prentiss shall brake his prentiship & desert his Master’s service or die within the yeirs of his prentiship yet notwithstanding it is statute the Master shal not be frie to take ane oyr(other) prentise untill that sd sex yeirs expyre.”

This explains the frequency of a Journeyman marrying his Master’s daughter. As the son or son-in-law of an existing burgess he could automatically qualify as a Burgess himself. It suited the Master equally well because it also meant that he could keep the business in the family. Also, as the son-in-law, his Burgess fees to the Burgh and his Masters fees for entry into the Craft were both reduced. Everyone appeared to be happy, although there is no record of what the poor daughter thought about the arrangement.

ONE thing that is unique about the Dyer Craft is the knowledge of a body called the “Dyer Lads.” This appears to have been based on the Acts of the Dyers themselves. The book was opened on 15th September 1711. This is the only trace of such an organisation in any of the Trades and so is quite unique. To date no comparable organisation has been found anywhere in Scotland. Like the Trade itself, there was an oath to be taken on entry and Rules for their Members included the knowledge of the secret “knock, chap and whistle.” They elected their own governing body. Their Deacon when chosen, was required to pay the sum of two shillings and six pence to entertain the brethren, and if he refused office he was to be fined one shilling. The number of names in this book from 1711 until 1770 totals 147. At the opening of the book, names were copied from an earlier book, and when the record of apprentices to the Craft ends in 1825, a grand total of 258 people had been recorded.

The Laws of the Dyer Lads are all concerned with work discipline. Fines are listed for fighting, coming to a meeting without his long coat, working without wearing his apron, “feakink” with the wrong side of his wrapper inmost, swearing, if he wore a clout on his apron and it did not have red and white strings, raising cloth to the wrong end, cutting his hand and the blood falling on cloth or hooks, leaving his scissors on the cloth when he went out, letting them fall off the board, putting them with the bowls uppermost, having more than one colour of flocks caught in the scissors, taking his scissors to be ground and not cleaning them, pressing cloth on the wrong side, and many others.

Alex. Warden, the author of “Warden’s Burgh Laws”, until now the leading authority on the Trades, suggests that the Dyer Lads formed this body and regulated it entirely of their own accord. However, since all the penalties are connected with work discipline and good practice in learning the craft, it is much more likely to have been set up by the Masters themselves as a kind of training manual. Surely the ‘Lads’ would not punish one another for such misdemeanours? If there was only one apprentice to each Master how would they find out that there were two threads of different coloured material stuck in someone’s scissors? This smacks much more of punishing the apprentices throughout the Craft to a scale of charges laid down by the Masters, for their own benefit, as well as training the apprentices. Their astuteness was in setting up an organisation, making the lads appear important and have a Deacon like their Masters and in allowing the Lads to administer it for themselves. The fact that this Book was kept with the Records of the Craft also points to this conclusion.

In 1560, the large shears with which the fullers cropped the surface of cloth were costly. Hew Nesbit, burgess of Edinburgh, pursued Andro Smyth and Patrik Henderson “for the soum of thirty-four shillings for ilk pair of nine pair of waulkers’ shears, coft and receivit be them frae Hew.” This payment they were decerned to make; and besides, Hew “protestit for costs, skaiths, dampnages, and interest susteinit be him in the action.” These shears required frequent sharpening, and a house was provided with necessary implements for doing this. In 1560, payment “is made in name of the brethren of the waulker craft, of certain mail for ane house wherein they grand their shears.” The records of the Hammermen show that about a century later, that craft took charge of the sharpening, and “furnishit and maintained ane grindstone for the grounding of waulkers’ shears, the price of ilk pair to pay two shillings;” and they protested against any others “setting up a stone attour the town” for that purpose.

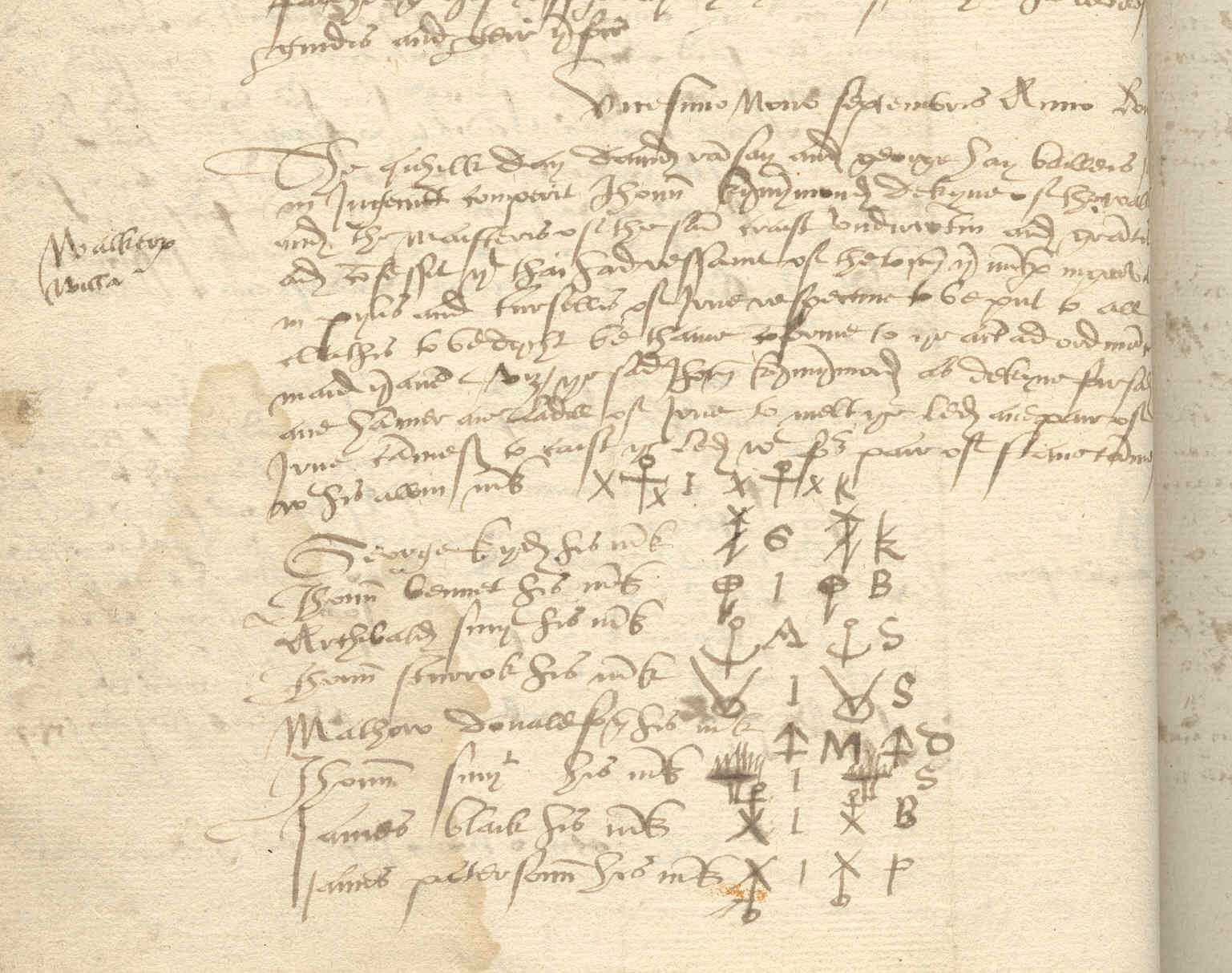

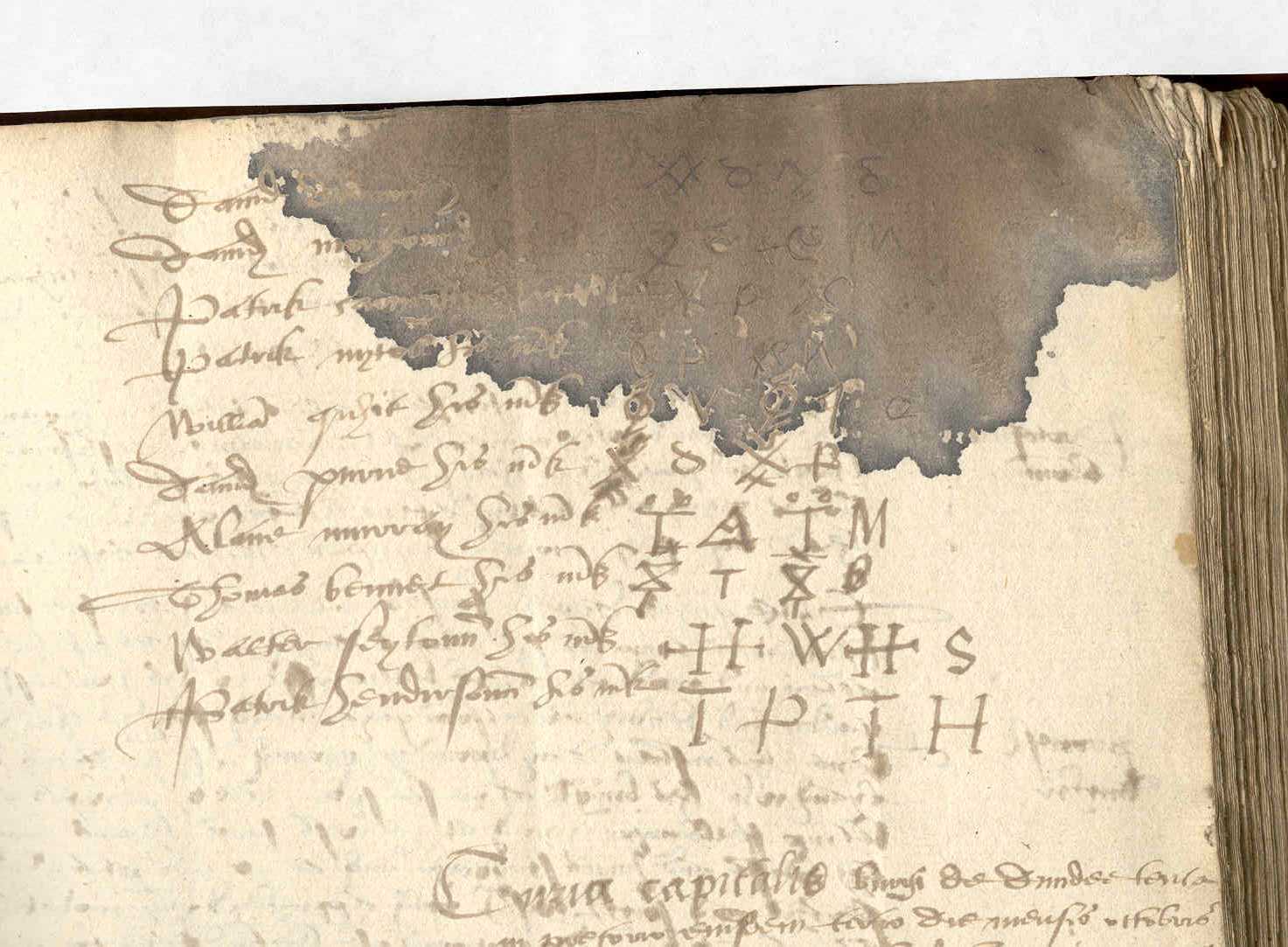

In common with other Trades, although the Dyers made their own statutes, their standards were in effect laid down by the Crown. For example there is a record of the various marks, which were given to the fullers for stamping their cloth in verification of its quality. It was pressed into a lead seal with a hole in it where a small part of the end of the cloth would be put through. Moulds put on the top and bottom were then pressed into the lead blanks. There were two trademarks, one was the man’s initials and the other his personal trademark, which was an arrangement of straight and curved lines.

The lead blanks were cast in two discs one having a little central projection in the middle and the other a hole. When the upper and lower dies were put in place they were struck with a hammer, producing the final seal. As far as is known there is no other drawing of these individual marks left in the country.

As early as 1514, the Dyers were mostly located around Dyers Close off the Murraygate. This was because of its proximity to the Meadow Burn, one of several which ran through the town and supplied the wells where the inhabitants drew their water. Care had to be taken about this because of the danger of contaminating the drinking water. 11 July 1521, a Dyer, “Will Wilson, with his awn grant, is (bound) that an he or any of his servants cast wad paist, noxious refuse from dye-stuffs, in the burn or dam to pay forty shillings to our Lady werk.” Again “whair tha John Bennatt’s servants has washen bonnets in the burn, the Bailies (resolve) to seek their acts (regarding this offence), and put them to execution.” At a later time “the Bailies decern Robert Bartie, a Flesher, to pay to the common werks the soum of eight shillings, and that because his servant wes convict for washing of pensches (animal intestines) in the Castle burn.”

In the Dundee Register of 1783, the Deacon, Boxmaster and Officer of the Trade, together with all their craftsmen had their premises in this area.

In common with the other trades the Dyers constantly fought against “unfree” people practising the trade. In 1707, they petitioned the council against “women doe encroach ye liberties of the said trade not only be taking in all sorts of cloath, worsett and dying ye same tae ye inhabitants and others vthne yer own houses but also they goe from house to house and dye ye said cloath and worsett qrby the said trade is verry near ruined w’tout remeadie mead to be had for that effect.” The council upheld this, but how effective it was we are not certain. It would have been very difficult indeed to apprehend the culprits and there is no record of this happening. However, it may well be that a Town Ordinance, proclaimed from the Tollbooth, was sufficient to keep it under control. The punishment for breaking any act of the Council was severe indeed and invariably included being “warded”, that is, put in the tollbooth jail.

Like the other Crafts the Dyers entered prominent people as Honorary Masters. In the case of the Dyers, however, there were fewer than the other Trades. This may have been because of their small numbers, their comparative poverty, or even the fact that they were considered less important in the eyes of possible recipients. In any event the small number included George Dempster of Dunnichen, MP for Dundee in 1761, Bailie Dowie and Provost Maxwell in 1768, Provost Alex. Riddoch in 1789, Robert Graham of Fintry, in 1790, Viscount Duncan of Camperdown and Lundie in 1798 and Sir John Ogilvy of Inverquharity in 1862.

As the years went on, the Craft struggled manfully to survive. Dyers were not voted on to the Town Council as representatives of the Nine Trades, partly because they could not get the dye out of their hands and arms and partly because the smell from them was quite disgusting. They were not considered suitable material to be Town Councillors. Even in the famous etching of “The Executive”, the Deacon of the Dyer Trade is apart from the others and although this can be nothing more than co-incidence, the other Trades get some amusement from it at the Dyer’s expense. This may also have been the reason why so few Masters were elected as Convener of the Nine Trades. The first is recorded in 1705, then 1723, 1729, and 1788. Not until 2001, some 213 years later do we find the next Dyer, Alex. Coupar, as Deacon Convener of the Nine Trades.

Eventually, after restrictions on the number of employees were removed, the Trade fell into fewer and fewer hands. The principal family in Dundee was the Stevensons, but by the late 20th century even that business closed. Finally, in 1996, the three remaining members met in the presence of the Deacon Convener of the Nine Incorporated Trades and the Clerk to the Nine and as other trades had done, agreed to modernise on the sensible and natural grounds that their trade in its purest form had changed. They therefore enacted that Masters could enter the Craft who were in any way connected with colour in its broadest sense. TODAY the modern Dyer Craft welcomes people in every field of colour and it is indeed a flourishing trade. Traditional Crafts are important, but with modern production, methods, techniques, and changes in society, the Dyer Craft has evolved and has taken its place as one of the important bodies in the development of the city.

Dyers are very proud of their heritage and at private meetings and on public occasions, wear a blue glove on their left hand and a small lapel badge of a sack representing the salt used in the dying process. The glove signifies the permanent colour of the Dyers hands, and the badge the bag of salt seen in the Crest of the Craft on the front cover of this booklet.

Like the others, the Dyers are very aware of the position they once enjoyed in the city. They have shared in the expansion of Dundee from its early days as the second city of Scotland. Dundee was renowned for its trading links throughout the world, and had a population of around four to six thousand at a time when Glasgow counted its numbers in hundreds. No decisions could be made by the Town Council concerning money without the agreement of the Trades. The Convener was required to audit the Burgh Accounts. The Trades, including the Dyers, had representation on every body of importance, from the council itself to the Harbour, the Hospitals, the Grammar School, the Electric, Water and Gas companies, the Morgan Trust and many others. Dundee was the first city in Britain to have electric lighting in its streets.

Mention has already been made of the Trade opening its membership to Masters working in colour. Since that decision, in 1996 we find Masters involved in Architecture, Sculpture, Printed Plastics, Newspaper Design, Photography, Textiles, Computing Game Design and Artists in its ranks. The Craft is still willing and anxious to increase the range of its membership, whilst maintaining the integrity of its original aims and objectives. Tradition is indeed important, but so also is the future.

All of these Masters, despite their diversity, are working in colour of one kind or another. There is no question of this member of the Nine Incorporated Trades of Dundee ever being in danger of losing its place through a lack of numbers. In recent years the Dyers have tended to stay in the background, carrying on their work by charitable donations and helping in the training of craftsmen of every Trade. In the last few years they have realised that they should raise their profile again. They feel that there is a need for a body having a non-political membership with a history of service to the community second to none to help carry forward the development of our city.

This they will do, and the Craft is looking forward to a future at least as long and valuable in our proud City as it has had over the last seven hundred years or more.

The original Craft, which was a Member of the Nine Incorporated Trades of Dundee, was the Waulker Craft. They were the fullers of cloth.

The original Craft, which was a Member of the Nine Incorporated Trades of Dundee, was the Waulker Craft. They were the fullers of cloth. 1514-1604 Dyer Notes

1514-1604 Dyer Notes 1525 StMarks Altar

1525 StMarks Altar

1560 Walkers Shears

1560 Walkers Shears 1608-9 Edinburgh Waulkers

1608-9 Edinburgh Waulkers 1690 Privy Council

1690 Privy Council 1695 Protestation Agd Walkers

1695 Protestation Agd Walkers 1818 Claverhouse Mill

1818 Claverhouse Mill 1857 Dundee Courier 18 March

1857 Dundee Courier 18 March Biology

Biology Regiam Majestatem

Regiam Majestatem

Waulk

Waulk Waulking

Waulking Dyers Documents and Pictures

Dyers Documents and Pictures